If you’ve seen videos of composting toilets or even used one at a State or National Park, you know that they don’t require water to function, but might be wondering exactly how does a composting toilet work?

In addition to conserving water, some composting toilets don’t require electricity (or can run off minimal amounts of solar power), so they’re especially popular with off-grid dwellings like tiny homes, RVs, sailboats, houseboats, cabins, and other unconventional housing types. I’ve personally had a composting toilet since 2016, so I have a lot of experience with how a composting toilet works, some of the benefits, and the drawbacks.

What is a Composting Toilet?

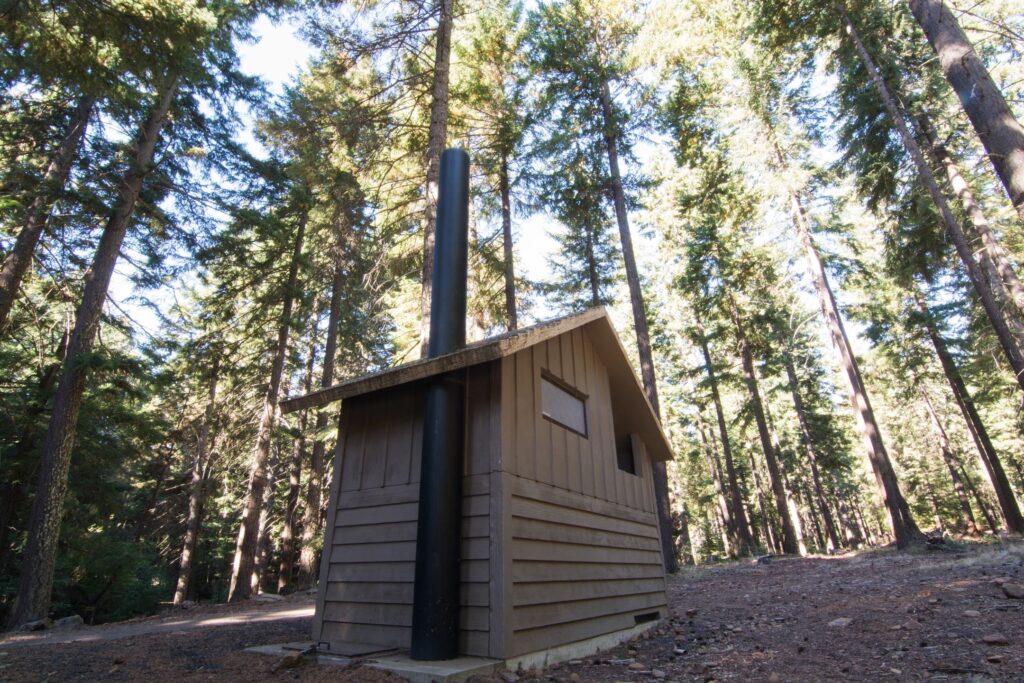

A composting toilet breaks down human waste through a natural decomposition process. Unlike traditional flush toilets, which require excessive amounts of water to process, composting toilets do not require any water. Composting toilets treat the waste right on site – in your toilet (or composting system) – so there’s no involved processes of sending wastewater elsewhere. They’re frequently used in off-grid properties, cabins, boats, tiny-homes, and parks where plumbing isn’t a reality.

A compost toilet is also very cost efficient. Flushing a typical conventional toilet costs between 1.3 cents per flush, and the average person uses the restroom about seven times per day. Multiply that by 365 days per year, and using that flush toilet is costing about $3,321 annually – and that doesn’t factor in all you double (or triple!) flushers out there.

There are many environmental benefits to using composting toilets, the main one being water conservation. Traditional residential flush toilets are the main source of indoor water consumption in residential homes, with older toilets using as much as 6 gallons per flush (newer models average around 1.6 with WaterSense models using about 1.28). Although we’ve all become accustomed to these types of toilets, we’re flushing precious freshwater down the drain instead of conserving it. Curious to learn more about these waterless wonders? Read on!

How does a Composting Toilet Work?

A composting toilet works by breaking waste down through an aerobic decomposition that utilizes materials like sphagnum peat moss, sawdust, coconut coir, and other natural materials.

It’s similar to the process in a composting tumbler that you’d used for vegetable scraps, eggs, banana peels, and coffee grounds, except they are designed to resemble and function like a toilet. Although compost from fruits and veggies can be used on the gardens, using human compost waste on gardens is not advised due to the potential for pathogens. Waste is aerated by “tumbling” it using a hand crank to help decompose the matter inside. Heat is generated as the waste breaks down.

Types of Composting Toilets

There are two main types of composting toilets (with different variations, so I’m generalizing here): a self contained composting toilet or a central system.

Self-Contained Composting Toilet

A self-contained composting toilet. This is the type I have on my sailboat. It’s a smaller (and cheaper) unit than a central composting system.The installation is also much simpler too. With this system, you must separate the liquids and solids – which is often done through two distinct storage areas. One has composting material like coconut coir or peat moss, another is just a tank for urine.

Rule number one: don’t pee in the peat moss chamber! Although you can – technically – toss toilet paper in these, the chambers aren’t that large, so toilet paper consumes a lot of real estate. It’s best to put the paper in a small bathroom garbage can. After you do your business, you turn a crank that stirs the compost up. For one to two people, the urine tanks on these must be emptied every two to three days with regular use and the waste (compost) chamber needs to be emptied about every month, or until it’s really difficult to turn the crank.

Central System

These are much larger (and more expensive) units that can be installed under the bathroom in a home. Because these central systems require a large amount of space for storage – they’re rooted, and can’t be used in RVs, boats, conversion vans, or other moving homes.

They feel similar to traditional toilets in that all the waste – urine, feces, and toilet paper – goes down to the tank. When the tank fills up, it all moves into a different chamber and excess liquid (urine) is drained out to another tank, grey water system, or it evaporates. Warm air is pulled into the waste chamber to assist in the composting process. These chambers must be emptied about every six months.

Do Composting Toilets Smell?

Self-contained composting toilets, for the most part, smell like dirt. There’s an initial odor when you first “do number two,” but, when working properly, the fan sucks the air outside of the unit (usually out a window or tube to the outdoors). They don’t have that awful “boat holding tank” odor that lingers or that porta-potty smell.

I prefer a composting toilet to having a holding tank for that reason. I’ve also heard horror stories from other boaters about pump-out services that didn’t go so well. I don’t have to rely on someone to come by with a suction hose with a composting toilet, and the solid wastes only have to be changed about every six weeks (we’ve definitely pushed it longer than that though). That said, the urine tank has a strong odor that isn’t really noticeable during normal use since the tank remains shut.

However, when it’s time to empty it, the smell of the urine tank is absolutely, positively, foul. I suggest not having guests anywhere near the area when it needs to be changed. TRUST ME. It’s gross. I also highly recommend having more than one urine tank for self contained toilets like Nature’s Head (which I have) or AirHead (another popular brand) because they have to be changed every 2-3 days with regular use. That’s the drawback.

A central system puts some distance between the toilet and the tank, but since composting generates heat (and heat rises) it’s possible for odors to creep up the exhaust pipes into the bathroom. To combat this, install a fan to keep sending odors in the opposite direction. With the proper installation, central systems shouldn’t have an odor. You don’t have to deal with frequently emptying a urine tank with a central system.

Interested in Learning More About Composting Toilets?

We’re just scratching the surface with a general overview and common questions about composting toilets. Stay tuned for more articles on composting. I’m working on a deep dive review of my Nature’s Head toilet – after 7 years of use — the good, the bad, and the downright gross. Coming soon!